EX – Stop Ignoring the Cost (1)

My last newsletter explored the financial ramifications of overlooking employee experience within our organisations. According to the Gallup State of the Global Workplace Report 2024, disengaged employees cost the world $ 8.9 trillion, which represents 9 percent of the global GDP.

I developed a calculator to assess your costs based on Gallup's figures. 17% of employees are actively disengaged, and each disengaged employee costs the company 18% of their annual salary.

The figures are quite scary. For example, if you are a US company with 1000 employees, 170 are actively disengaged. Disengagement costs 18% of an employee’s salary = $10,698 per employee. Total cost per year = $10,698 x 170 = $1,818,741.

Can you afford to ignore the price of disengagement?

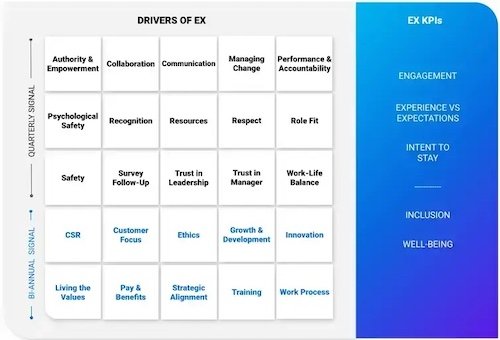

I outlined how feedback on employee experience can be gathered beyond the annual or biannual survey.

I also referenced the key drivers of employee experience as determined by Qualtrics.

This week, I will focus on two of these drivers that, based on my experience, should be in your strategic objectives to improve the employee experience. That being said, you will note that I am referring to other drivers in this matrix within each focus driver. They do not operate in silos.

1. Trust

Qualtrics splits the key driver of trust into “trust in leadership” and “trust in manager.” They define the leader as the c-suite, and employees develop a sense of trust in leadership when they see good decisions and consistent, ethical behavior at the head of the organisation. The manager is the person to whom employees directly report, and trust is established when they are seen as dependable, fair, honest, and genuinely caring.

In my opinion, trust must permeate every part of the organisation and be an integral part of company culture. Leaders and managers must take deliberate action to demonstrate trust through their words and behaviours, but those actions must penetrate every aspect of the organisation.

Trust must be a value lived by everyone.

A definition of trust is ‘a firm belief in the reliability, truth, or ability of someone.’ Without trust, there is no team. When there is trust in a team, each team member knows they can rely on each other to do the right thing. They believe in each other’s integrity and strength and know that they have your back. The team members feel safe with each other; they can be open and honest with each other, take appropriate risks and show their vulnerabilities. They share knowledge and communicate openly.

There is a myriad of ways to build trust within the organisation.

Transparency

No one trusts someone who hides behind platitudes and untruths. When you are transparent, you are open and honest with each other. Transparent leaders involve teams in decision-making and share information widely, ensuring everyone, regardless of location, is informed and involved.

They do not treat their employees like children and assume they will not be able to handle the information shared. Your employees are adults and just as mature and capable of handling information as you are. Of course, there may be circumstances when it would not be appropriate to share information with your team but that should be the exception.

When you are transparent, you not only give feedback but actively seek it out for yourself. You are open about wanting to be better at what you do and ask for honest feedback. You know that there will be no judgment or reprisal if the feedback highlights a weakness in the someone. You do not get defensive or angry – you embrace feedback as an opportunity for growth. Most of all, you act upon it.

Psychological safety

The foundation of psychological safety is trust. There is also the chicken and egg conundrum. When you create an environment of psychological safety, trust increases.

Psychological safety means employees will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes. Every contribution is welcomed and listened to with respect. Employees trust their leader and each other to hear what they have to say without any fear of repercussion or reprisal. Each time that happens, trust grows stronger.

Living the values

Trust exists when the organisation has positive values that resonate with its employees. Values are co-created, and everyone lives by them. They are evident in language, behaviours, and decisions. Shared values build trust.

When an employee does not live the values, it can be called out. A culture of respect, transparency, and trust allows this to be done positively. An initial, informal, and relaxed chat may be all that is needed to remind a person of the values and how their recent behavior has upheld those values. You must be nonjudgmental, open-minded, and empathetic when you have this conversation.

You must not assume that the person is deliberately not living the value, as you do not know what else is happening in their professional or personal life that has caused a change in language or behavior. I strongly urge you to watch this 2:14 video, “20 Minutes Earlier,” as a reminder that you do not know what someone else is dealing with. Be kind. Offer support.

If the conversation does not resolve the situation, you will need to escalate and discuss it with the person’s line manager, who may, in turn, involve HR.R.

Communication and listening

Trust occurs when communication is unambiguous. Being transparent, open and honest fuels a culture of trust. Everyone knows when communication is authentic and when it is not.

Communication must be multidirectional, from employee to employee, employee to leader, and leader to employee. It must ensure that the right people have the right information at the right time.

It is important to remember that there is no such thing as over-communication. No one ever left an organisation because they were told too much!

When everyone practices active listening to ensure they truly hear what each other has to say, it reinforces trust. Active listening means being present, really hearing what people are saying, validating your understanding by repeating what was said, encouraging people to share more by asking them questions, and prompting those who are not participating to speak up and get involved. Active listening involves avoiding distractions and watching for verbal and physical cues about how the other person is feeling.

Performance and accountability

Everyone must know what is expected of them in their role and what they will be held accountable for.

Trust is established when employees are measured on the value they deliver, not the volume they deliver. They must be measured on outcomes delivered, not hours spent at a desk.

Trust is undermined when poor bosses monitor the time employees spend at their keyboards. Leaders should trust their employees and grant them the freedom to work where, when, and how they choose. You employ responsible adults, so treat your workforce accordingly. When employees are monitored under the false belief that it reflects their productivity, all you convey is, “I do not trust you.”

2. Authority and empowerment

Everyone must feel they have the appropriate freedom to exercise their judgment and do their jobs to the best of their ability. Everyone must have autonomy at work - a widely recognised driver of positive employee attitudes. When employees are genuinely given authority and empowerment, they feel trusted.

Employees must be given clear goals and then allowed to achieve them in the manner they deem best. The leader does not abdicate responsibility but is always on hand to remove obstacles and provide guidance and support when needed. When leaders set goals and have clarified that they are understood, they must get out of the way.

There is no place for micromanagement. When someone is micromanaged, they are being told they cannot be trusted to achieve an outcome without step-by-step instructions.

When there is ownership, there is accountability. There is no waiting around to see if someone else will do something. There is accountability for the outcomes being delivered to the highest possible quality and on time. When you take ownership, others trust you to do the right thing.

Employees with authority and empowerment will feel free to reach out to others for support and collaboration. They will innovate and put their own stamp on their work. They know it is okay to take risks (within parameters) and experience setbacks.

Autonomy means everyone has the freedom to make their own decisions and take ownership of their work.

A few years ago, I wrote an article exploring empowerment, autonomy and delegation. I discussed the need for clear parameters around decision-making so that employees do not feel they are being set up for failure. They have guidance regarding what decisions may require additional input.

“Often, these are called guidelines or guardrails. Just as the guardrails on the road are there to prevent us from going off the road, guardrails around decision-making are there to keep us from making risky decisions.

How do your employees know what decisions they can make without recourse to you?

You can apply the ‘Waterline Principle’ instituted by American engineer and entrepreneur Bill Gore, the co-founder of W.L. Gore and Associates, the maker of innovative products such as Gore-Tex fabrics.

Imagine your organisation is a ship and you are the captain. You can empower employees to make decisions if they are shooting above the waterline. The decisions won’t sink the ship so the risk can be sanctioned. If the decision should go awry and results in a hole in the side of the ship above the waterline, it can be fixed.

If the decision is shooting below the waterline, it is a risk that cannot be sanctioned, as it could blow a hole in the side of the ship that is below the waterline and could sink the ship. Below-the-waterline-decisions need to be referred to the ‘captain’ so that risk can be assessed, and the right decision made.”

“As the captain, you can also define where the waterline sits based on factors including an employee’s position, experience, and level of expertise. A junior employee will have a different waterline to that of your senior managers.

The waterline principle can also be applied to deciding what issues need your attention as opposed to those that can be left to your team to resolve. If an issue has occurred, the criticality can be determined by asking whether the damage is above or below the waterline.

If something goes wrong above the waterline, such as a broken computer or a jammed door, the ship will not sink, and therefore, the issue can be dealt with by your team and does not need to be referred to you as the captain. If something goes wrong below the waterline, such as engine failure, the ship could sink and cause injury or loss of life. This decision requires your attention. Once again, your team will be far more effective and efficient by following this principle.”

Summary

If you genuinely want to improve the employee experience, you must build a culture of mutual trust and empower everyone in the workplace.

Next week, I will explore three more of the key drivers of EX.